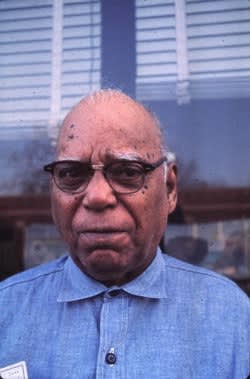

Joseph Yoakum American, 1890-1972

Official records indicate that Joseph Yoakum’s birthplace was Ash Grove, Missouri, but he liked to say that he was born on an Indian reservation in Window Rock, Arizona. His mother, born into slavery in the 1850s, was of African, French American, and Native American descent, and his father was a farmer of Cherokee and Creek descent. Yoakum was one of many children and received very little formal education. He grew up on a farm near Walnut Grove, Missouri, from which (according to his own account) he escaped at age nine to join the Great Wallace Circus. For the next decade he led a nomadic life, traveling across the United States and abroad with other itinerant shows—Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West and the Ringling Brothers, among others—for which he worked tending to horses and posting bills.

In 1908 he returned to Missouri, where he met his first wife. The couple married and had five children, and Yoakum settled down for the next ten years, working as a coal miner to support his family. In 1918, however, he was drafted to serve in World War I as part of the all–African American 805th Pioneer Infantry repairing roads, bridges, and railroads, and he was later stationed in France. After the war he returned to his nomadic lifestyle rather than his family, working as a railroad porter, a sailor, and an apple picker, among other jobs. He traveled extensively and claimed to have visited every continent except for Antarctica. At one point in the 1920s he moved to Chicago, where he remarried in 1929 and remained for the rest of his life. In the mid-1940s Yoakum began to experience symptoms of dementia and lived for a time in a psychiatric ward. A few years later he was widowed and residing in a housing project for the elderly until he moved in 1966 to a storefront on Chicago’s South Side. Sometime between the early or mid-1950s and early 1960s, no longer able to work a regular job, Yoakum started making art.

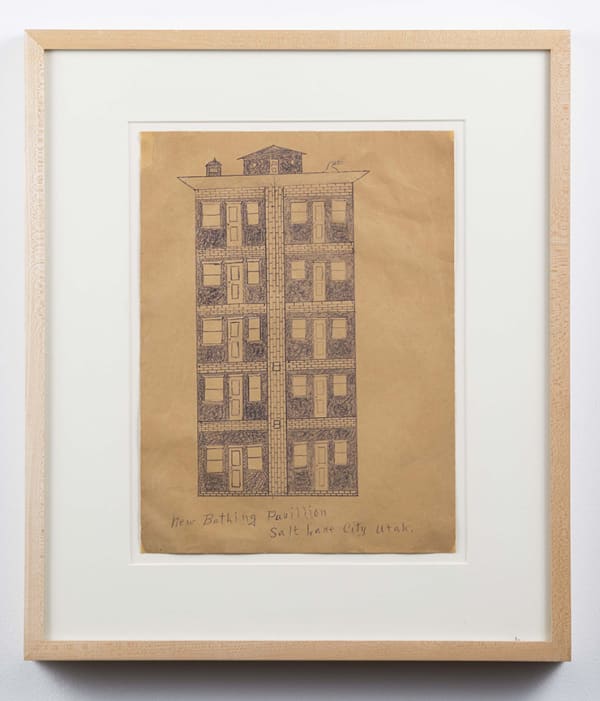

His early drawings were primarily monochrome pen-and-graphite works on small sheets of white or manila paper, but he soon started working in larger formats and experimenting with color. Yoakum made more than two thousand drawings, most of them landscapes of mountains and water. A unique fusion of reality and imagination, these compositions are dreamscapes where Yoakum’s memories and visions merge. He used a variety of encyclopedias, atlases, and travel books as reference material, but he described his process as a “spiritual enfoldment.” With a ballpoint pen he sketched his winding outlines freehand, delicately tinted the negative spaces with colored pencils, pastels, watercolors, or chalk, and then buffed the surface with a bit of toilet paper to give his drawings an ethereal finish. He signed and dated most of his works and often wrote small indicators of the locations depicted although the scenes were generally not identifiable.

Yoakum was quiet and introverted, his religious and artistic ethos grounded in the belief that God and nature were one and the same. At some point after moving to the South Side, he decided to hang some of his drawings by a string along his window, and they caught the attention of a neighbor named John Hobgood, an anthropologist and professor at Chicago State College (now Chicago State University). Hobgood’s purchase of several drawings led to a small exhibition in the basement of St. Bartholomew’s Lutheran Church, whose pastor sent a letter to the Chicago Daily News, which ran a profile on the artist—after which fascination with Yoakum’s artwork snowballed.

In 1969 Yoakum’s work was included in an exhibition at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art, and in 1971 his drawings were shown at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Shortly before he died, the Whitney Museum of American Art mounted a solo exhibition of his work. His drawings are in the Museum of Modern Art, the American Folk Art Museum (New York), the Milwaukee Art Museum, Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art (Chicago), the New Orleans Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington, D.C.), the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the abcd Collection (Paris).