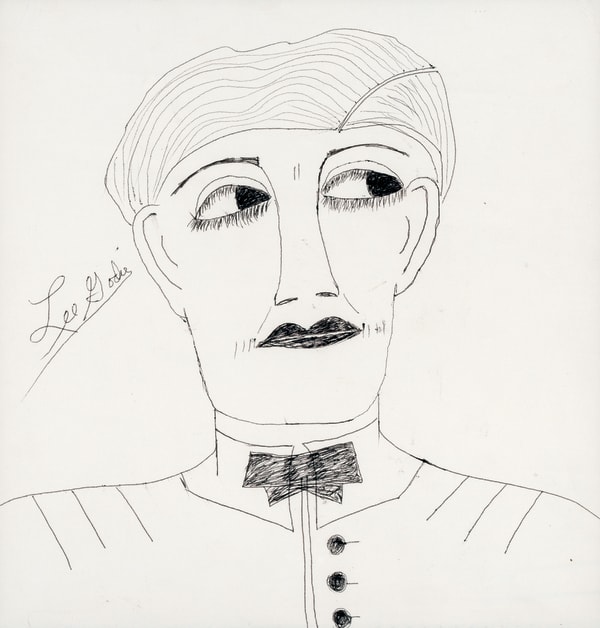

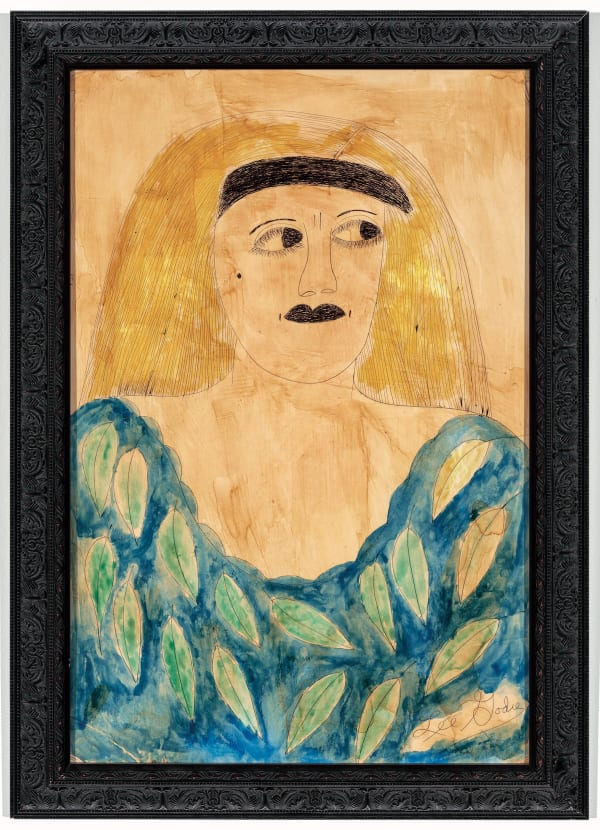

Lee Godie American, 1908-1994

One day in 1968 Lee Godie appeared on the steps of the Art Institute of Chicago with a bunch of artwork to sell. She was homeless by choice and referred to herself as a “French impressionist” and she remained a centerpiece in the city’s cultural landscape until shortly before her death. Godie sold her drawings and paintings to passersby (but only if she liked them) for very little money and in time garnered the attention of the art world. She was wary of talking about her life before her self-fashioned debut as an artist, but what is known is that she was born Jamot Emily Godee and was married in the 1930s. She had three children, one of whom died in the early 1940s. Divorce followed, as well as the death of her eldest daughter, who contracted diphtheria. The two deaths apparently led her to believe that illness could be cured by faith rather than medicine. By the 1960s Godie lost her home and took to the streets, becoming a full-time performer, constantly disguised behind many alter egos. As Anna Saunders described her in a 2013 Telegraph article, “Colourful and unpredictable, she was as likely to appear wrapped in a toga and fur coat one day as in full safari regalia the next. To downtown workers she was a local character—a beloved part of the city’s gritty, urban fabric. . . .”

Godie’s subjects included half-bust portraits of imagined characters, especially big-eyed women with impossibly abundant eyelashes, stylishly outfitted in patterned or 1920s fashions that flow into the picture’s background. She also portrayed passersby from her spot at the Art Institute, friends, famous people, herself, as well as still lifes, birds, and other animals. She used various traditional and found materials and invented a format called “pillow paintings”: two drawings stitched together and stuffed with newspaper. Godie also made many photobooth self-portraits assuming different personas by painting her face, displaying props, and wearing singular attire. She also often altered the prints, scratching the surface and coloring them. These images are a window into the dichotomies of Godie’s life on the street—the hardships and the aggressive fantasy, her undiagnosed mental state and her indefatigable shrewdness for survival.

Press coverage of Godie during the last years of her life caught the attention of her surviving daughter, Bonnie Blank, who found her mother and in 1991 was appointed her legal guardian (by then, Godie was suffering from dementia). That same year, Richard M. Daley, Chicago’s mayor at the time, proclaimed September “Lee Godie Exhibition Month,” urging residents of the city to pay homage to the artist. Godie had two solo exhibitions at the Carl Hammer Gallery (Chicago, 1991 and 1993), a retrospective at the Chicago Cultural Center in 1993, and her work was included in Art in Chicago 1945–1995 at the Museum of Contemporary Art (Chicago) in 1996. More recently, Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art mounted the exhibition Finding Beauty: The Art of Lee Godie (2008). Godie’s works are in the permanent collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington, D.C.), the American Folk Art Museum (New York), the Museum of Contemporary Art and Intuit (Chicago), the Milwaukee Art Museum, and the Arkansas Art Center (Little Rock).