Martín Ramírez Mexican, 1895-1963

At age thirty, Martín Ramírez, a faithful Catholic and a practiced horseback rider, left his native Jalisco, Mexico, to look for work in California. As Ramírez’s biographer the sociologist Víctor Espinosa recounted, Ramírez left behind a wife and four children while Mexico was immersed in the aftermath of the revolution, and he effectively walked into a maze never to find his way out. Before the Great Depression, he worked in mines and on the railroads in northern California and began drawing on the margins of his letters home.

In 1931, he was institutionalized for presumed manic depression and later diagnosed with catatonic schizophrenic. In clinical examinations, he repeatedly said that he could not speak English and that he was not insane. Thereafter, he expressed himself through art and spent the rest of his life in psychiatric facilities—first Stockton State Hospital, from which he attempted escape, and some years later he was placed in the DeWitt State Hospital in Auburn, CA. The drawings he made at DeWitt were preserved by Tarmo Pasto, a painter and professor of art and psychology who gave him materials (apart from those he salvaged himself), and by Max Dunievitz, the physician at the ward where Ramírez lived out his last years.

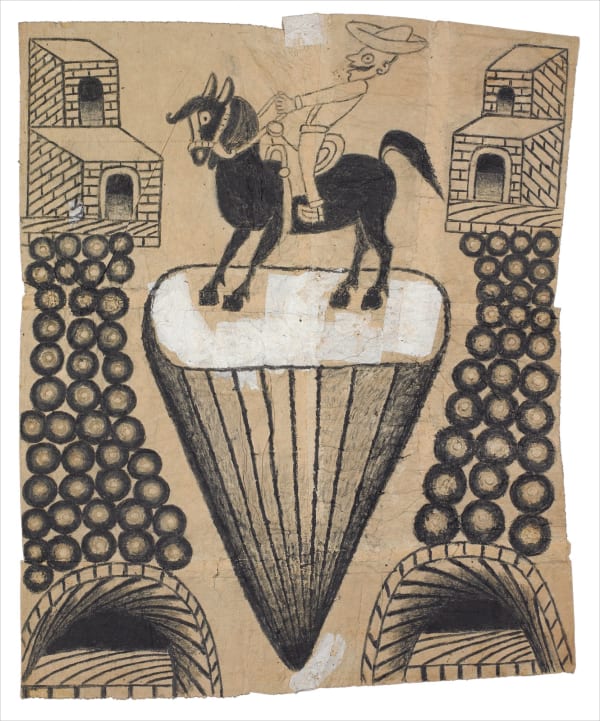

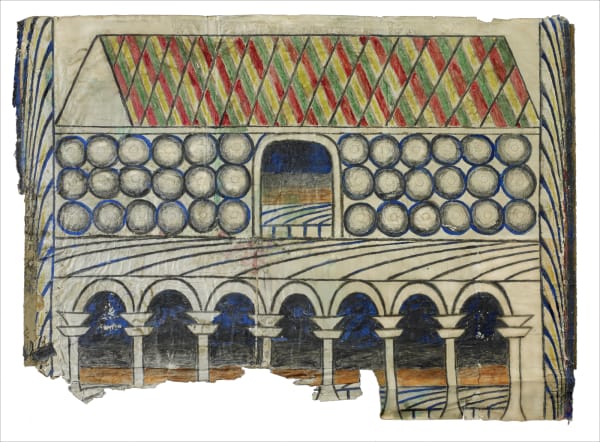

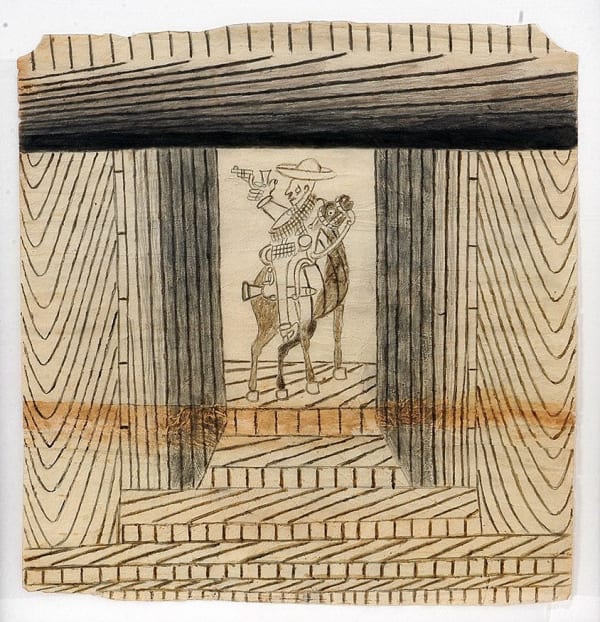

Ramírez’s work shows a compulsion to encapsulate and a concern with boundaries, and he often merges alienating landscapes with Mexican iconography. His assemblages, Madonnas and caballeros, animals, and trains framed within visually reverberating lineal shapes are like missives from an alternate world, familiar yet eerie. Profound isolation reaches a point where representation fails to meet life and becomes something else altogether. Ramírez is indisputably among the great self-taught masters of the past century, and the formidable artistic will expressed in his opus is evidence of the tragic personal wreckage of confinement and psychological and cultural segregation.

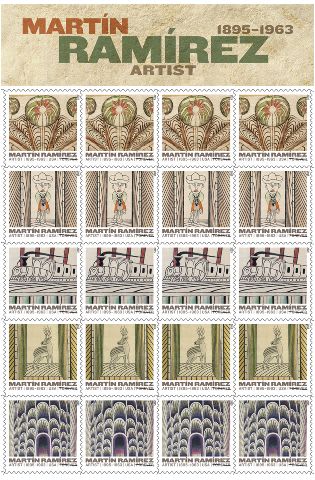

In his lifetime, Ramírez was the subject of four solo exhibitions, at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento (1952), the Stephens Union at the University of Berkeley (1952), the Mills College of Art Museum in Oakland (1954), and the Joe and Emily Lowe Art Center at Syracuse University (1961)—all of which excluded his name because of policies aimed to protect the privacy of psychiatric patients. A decade after Ramírez died at age 68, the art dealer Phyllis Kind and artist Jim Nutt introduced his work into the art market. There have since been major retrospectives of Ramírez’s work, including at Moore College of Art (Philadelphia, 1985), the Centro Cultural/Arte Contemporáneo (Mexico City, 1989), the American Folk Art Museum (New York, 2007), the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (Madrid, 2010), and the Institute of Contemporary Art (Los Angeles, 2017). His work is in the permanent collections of the Milwaukee Art Museum, the High Museum of Art (Atlanta), the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art (New York), and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (New York). In 2015 the United States Postal Service issued a set of five “forever” stamps featuring Ramírez’s work and honoring his life.

-

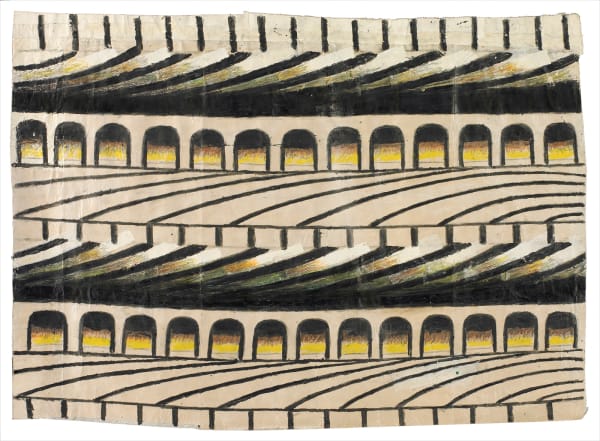

Untitled (Arches), C. 1960-63

Untitled (Arches), C. 1960-63 -

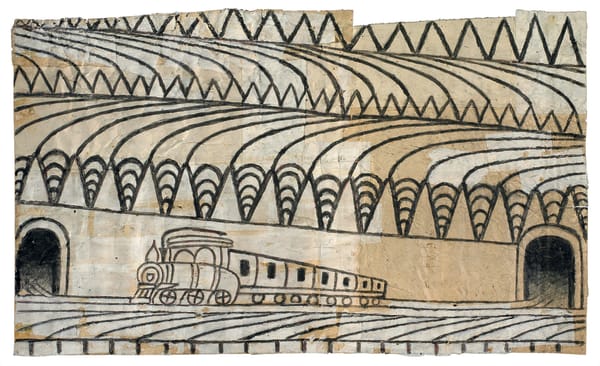

Untitled (Triangle Landscape with Train), c. 1960-63

Untitled (Triangle Landscape with Train), c. 1960-63 -

Untitled (woman in a red dress), c. 1960-63

Untitled (woman in a red dress), c. 1960-63 -

Untitled (Female Rider on Purple horse) , c. 1952-53

Untitled (Female Rider on Purple horse) , c. 1952-53 -

Untitled (Horse and Rider Hunting Rabbit), 1960-63

Untitled (Horse and Rider Hunting Rabbit), 1960-63 -

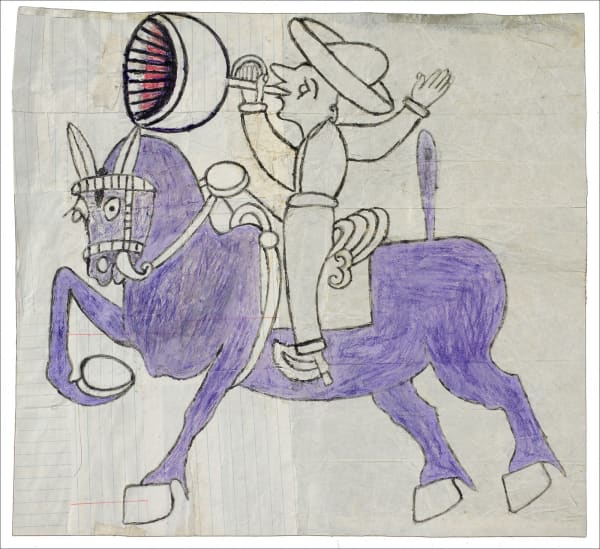

Untitled (Horse and rider with Bugle), 1960-63

Untitled (Horse and rider with Bugle), 1960-63 -

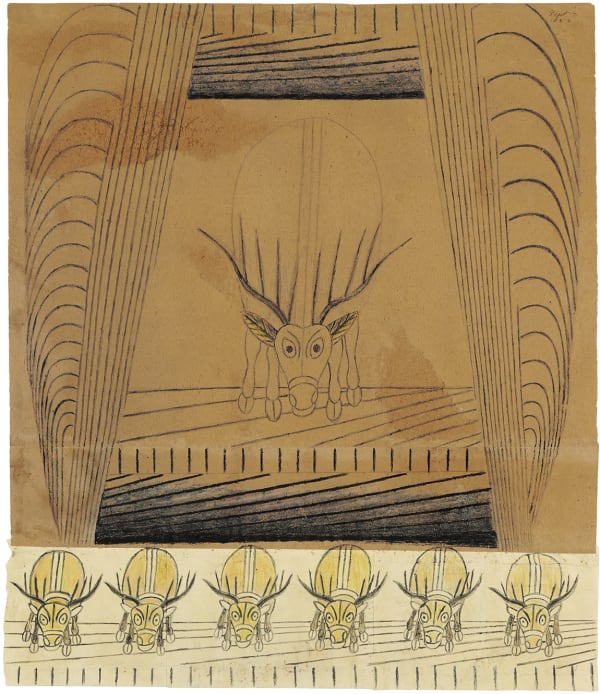

Untitled (Seven Stags), 1953

Untitled (Seven Stags), 1953 -

Abstracted Landscape with Horse and Rider

Abstracted Landscape with Horse and Rider -

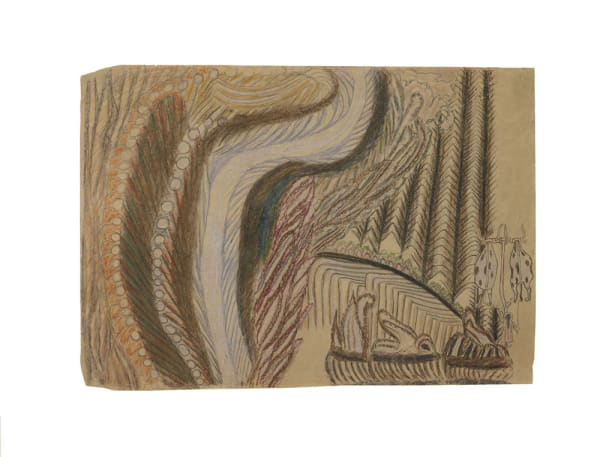

Abstraction with Colonade

Abstraction with Colonade -

Caballero

Caballero -

Church and Cross

Church and Cross -

Stamps

Stamps -

Untitled (Landscape with Oxen and Woman)

Untitled (Landscape with Oxen and Woman)