Mose Tolliver American, 1919-2006

Mose Tolliver was the youngest of seven sons in a family with twelve children. His father was a sharecropper and farm laborer in the Pike Road rural community, near Montgomery in the state of Alabama, where Tolliver lived his entire life. He attended school through the third grade and as a teenager worked gathering and selling produce for a truck farmer. He also worked as a house painter, a carpenter, and a plumber, and off and on cleaning up the shipping area at the McLendon Furniture Company, where in the late 1960s a crate full of marble fell from a forklift and crushed Tolliver’s left ankle, leaving him permanently unable to walk unassisted. After a period of drinking and depression he started to paint in earnest and developed his characteristic style.

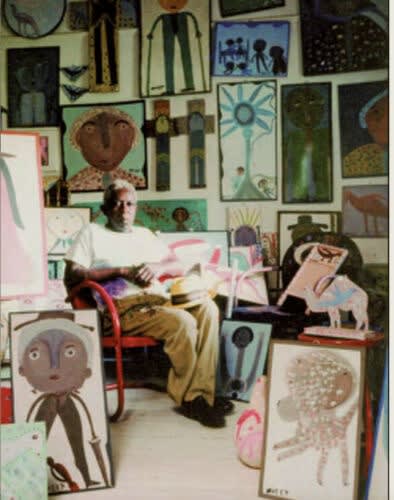

Tolliver began painting on any available surface (scraps from packing crates, Masonite, tabletops, and metal trays) and later on sheets of plywood with house paint. His color palettes, like his compositions, are clean and refined. Tolliver worked quickly and was extremely prolific, creating hundreds of pictures of birds, plant life, anthropomorphic figures, and people—including self-portraits with crutches and portraits of his wife. Many of his images are sexually suggestive (or “nasty paintings” as he would call them), particularly his “moose ladies,” or women hovering spread-legged over rounded objects that he called “scooters” or “exercising bicycles.” Tolliver’s visual vocabulary is whimsical and instantly recognizable: his brushstrokes are thick, rhythmic, and expressionistic; his figures flat and abstracted with exaggerated round heads, seen from a full-frontal perspective and generally dominating the entire picture plane. He often added a painted frame around his subjects and always signed them with the inscription “MOSET,” with an inverted “S,” a possible indication of dyslexia.

Tolliver began displaying his paintings on his front porch, where they got the attention of Mitchell Kahan, then curator of the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, which mounted a solo show of his work in 1981. In the exhibition catalog Kahan wrote, “The naiveté of the improbable and bizarrely constructed animals is comical in a charming way. The humor . . . results from the unintentional discrepancy between the painted image and the real-life source. . . . Often the humor is linked to elements of fantasy and eroticism.” In an article published in the Montgomery Advertiser in 1981, Robert Bishop, then director of the American Folk Art Museum, wrote, “You can hang him beside a Picasso, and you have the same kind of creativity and deep personal vision.” A year later, Tolliver’s work was included in the groundbreaking exhibition Black Folk Art in America 1930–1980 at the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.). Tolliver’s work is in the collections of the African American Museum (Dallas), the American Folk Art Museum (New York), the Birmingham Museum of Art, the High Museum of Art (Atlanta), Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art (Chicago), the Milwaukee Art Museum, the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, the New Orleans Museum of Art, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington, D.C.).