Bill Traylor American, 1854-1949

Although emancipated as a boy, Bill Traylor continued to labor until around 1908 on a neighboring plantation to the cotton plantation near Benton, Alabama, where he was born into slavery. By 1910 he was a tenant farmer near Montgomery.

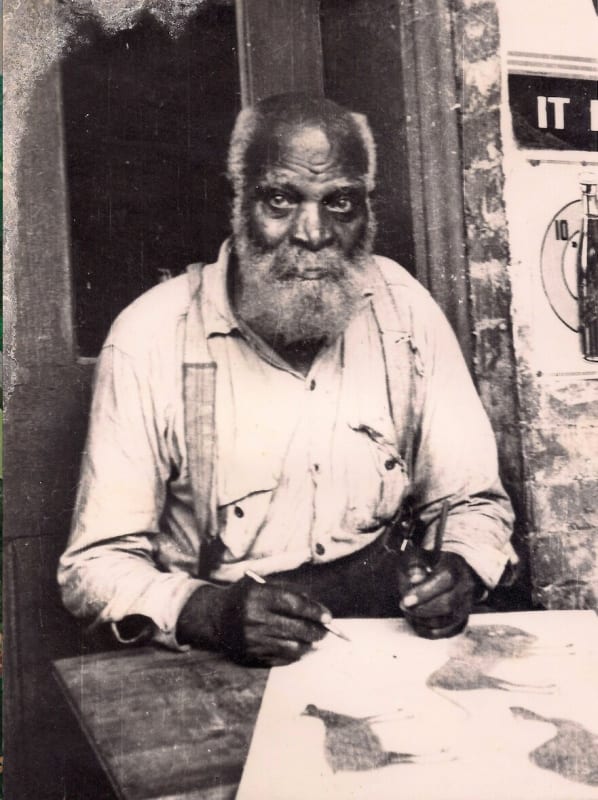

It was only when he was in his eighties and no longer able to do physical work that he started making art with materials that lay to hand, learning to write his name so he could sign his work. From 1939 to 1942, Traylor produced more than 1,200 drawings that are of crucial significance in American art and social history. Visitors to the black neighborhood of Montgomery, where Traylor had moved in 1928, according to a 1930 U.S. Census, after spending most of his life on plantations, could have encountered Traylor, a bearded old man sitting on a sidewalk on Monroe Street next to a Coca-Cola cooler, a drawing board across his lap—he drew all day and slept for free in the back of a funeral parlor. In 1939 Traylor caught the attention of a passerby named Charles Shannon—a young artist who led the New South cultural center with a group of progressive white artists in Montgomery. Shannon became Traylor’s friend and patron, safeguarding finished works and offering additional art supplies (though Traylor tended to prefer salvaged materials such as found cardboard, graphite, and poster paint).

Traylor’s imagery consists of laborers with hammers, drinkers with flasks, hunters with shotguns, dandies in hats, seniors with canes, rural pedestrians, and some anthropomorphic figures often overlooked. People quarrel and point, live poultry flap wings, and frightening dogs go on the attack; characters hide beneath or stand atop and stumble off structures; there is a lot of apparent pursuit and escape. Many things may be inferred from this dynamic, but Traylor’s message is not necessarily knowable. His simplified, modern figures, especially in works he referred to as “exciting events,” seem not to be straightforward depictions of what he may have seen but, rather, projections from the heart of his experience, distilled by memory. The abstract, minimalist figures and shapes in his work exemplify Traylor’s wildly original, true naïveté.

In 1942 Traylor interrupted his artwork when he traveled to several northern cities through 1945 to stay with a few of his children (all told, numbering some twenty-odd, according to Traylor). After he lost a leg to gangrene, the social agency that delivered his welfare check discovered a daughter living in Montgomery and suggested that he live with her, and he returned to Montgomery in 1946. Discouraged, Traylor lost all motivation to make art. He died at Oak Street Hospital in Montgomery a few days after summoning Shannon for a final visit.

Although Shannon had mounted an exhibition, Bill Traylor: People’s Artist, in 1940, the public at large did not know Traylor’s work until it was included in the 1982 exhibition Black Folk Art in America 1930–1980 at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C. His posthumous recognition has expanded steadily ever since, and today his work is in important private and museum collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Whitney Museum of American Art (New York), the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, and the High Museum of Art (Atlanta). A wide-ranging retrospective, Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor, organized by Leslie Umberger and shown from September 28, 2018, to March 17, 2019, at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., included several works from the Victor Keen collection and was accompanied by an extensive monograph that constitutes the most comprehensive study to date of Traylor’s life and art.

-

Untitled (Construction with Six Figures and a Dog), c.1939-42

Untitled (Construction with Six Figures and a Dog), c.1939-42 -

Untitled (Green Construction with Two Men and a Dog), c.1939-42

Untitled (Green Construction with Two Men and a Dog), c.1939-42 -

Untitled (Purple And Green Man With Umbrella), c.1939-42

Untitled (Purple And Green Man With Umbrella), c.1939-42 -

Untitled (Red, Blue, Black and Brown Construction), c.1939-42

Untitled (Red, Blue, Black and Brown Construction), c.1939-42 -

Untitled (Man Walking Dog), c. 1939

Untitled (Man Walking Dog), c. 1939 -

Black Cow, 1939-1942

Black Cow, 1939-1942 -

Black Dog

Black Dog -

Dog, Man and Drunk

Dog, Man and Drunk -

Men on Roof (crazy house with figures)

Men on Roof (crazy house with figures)